Optimal Stopping in Speed Dating

I came across this question when I was reading the first chapter of the book ‘Algorithms to Live By’. It’s a famous problem that uses the optimal stopping theory. The problem has been studied extensively in the fields of statistics, decision theory and applied probability. It’s also known as secretary problem, marriage problem and the best choice problem.In any optimal problem, the crucial dilemma is not which option to pick, but how many options to even consider. The problem proved to be a near-perfect mathematical puzzle: simple to explain, devilish to solve, succinct in its answer, and intriguing in its implications. I am going to present this problem under the speed dating scenario for easier understanding and use simulation to find the answer.

Introduction

Imagine you are going to attend a speed dating event at Ritz Carlton on Friday night, You have paid $500 to the event organizer and are determined to find an idea partner in this luxury hotel. However, this event is not only planned and optimized for yourself, there are some rules on the board to help running the event smoothly. The headache guidelines include: 1.The Boy/Girl arrvies sequentially in random order and you have only 5 mins to talk with each one of them. 2. Once you decide to pass the current partner, he/she is gone forever and cannot be recalled. 3.Once you feel good enough about the current person, You could exchange the phone number with him/her and you have to leave the event immediately. (The rules, of course, are not entirely reasonable in real applications) Since you have spent lots of money and energy to join this event, you also set a high standard for yourself: to find the best Boy/Girl in this event, no one less will do. And you are experienced enough to order the person you met from most admired to worst with no ties in 5 mins. So the question comes: what kind of strategy should you adopt to find the best candidate ? At which point should you decide to stop and exchange your phone number with the opposite partner? In my simulation, I assume there are 100 candidates joining this event

Simulation

library(ggplot2)

set.seed(123)

best_k <- function(Simulations_N, N) {

if (N == 0 || Simulations_N == 0) {

return("Number of Samples and Number of Simulations should be Greater Than Zero !")

}

# Index represents the stopping place, the number is the time you select the

# best candidate

quality <- rep(0, N - 1)

for (i in 1:Simulations_N) {

# Randomly generate N numbers which indicate the quality of the candidates

scores <- sample.int(N, N)

for (j in 1:N - 1) {

if (max(scores[1:j]) == N) {

# Fail to find a good partner

} else {

# Find the first candidate that we see who is better than all of the

# previous candidates

optimal_place <- min(which(scores[j + 1:N] > max(scores[1:j]))) +

j

if (scores[optimal_place] == N) {

quality[j] = quality[j] + 1

}

}

}

}

return(which.max(quality)/N)

}

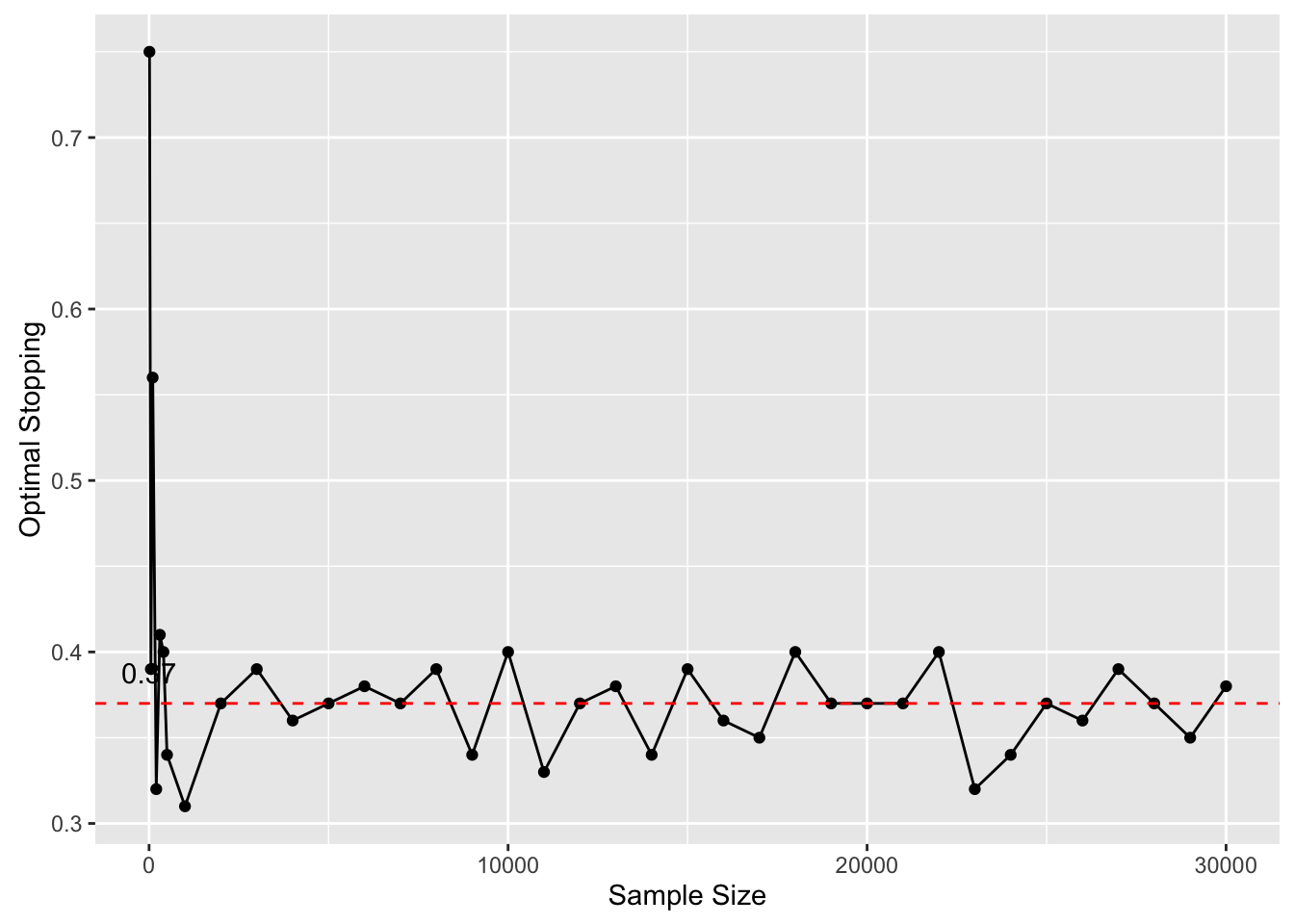

# Increase the simulation N and to see the convergent result

simulations <- c(10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, seq(1000, 30000, 1000))

result <- NULL

for (z in simulations) {

result <- c(result, best_k(z, 100))

}

qplot(x = simulations, y = result, geom = c("point", "line"), xlab = "Sample Size",

ylab = "Optimal Stopping") + geom_hline(aes(yintercept = 0.37), color = "red",

linetype = "dashed") + geom_text(aes(0, 0.37, label = 0.37, vjust = -1))

Whence 37% ?

This part is from the book “Algorithms to Live By” by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths

In your search for a lover, there are two ways you can fail: stopping earily, you leave the best choice undiscovered. When you stop too late, you hold out for a better choice who doesn’t exist. The optimal strategy will clearly require finding the right balance between the two, walking the tightrope between looking too much and not enough.

Intuitively, there are a few potential strategies. For instance, making an offer the third time an applicant trumps eveyone seen so far- or maybe the fourth time. Or perhaps taking the next best-yet applicant to come along after a long drought. But as it happens, neither of these relatively sensible strategies comes out on top. Instead, the optimal solution takes the form of what we’ll call the Look-Then-Leap-Rule. You set a predetermined amount of time for “looking” - that is, exploring your options, gathering data - in which you categorically don’t choose anyone, no matter how impressive. After that point, you enter the “leap” phase, prepared to instantly commit to anyone who outshines the best applicant you saw in the look phase.